What is Mach Number? Significance, Formula, and Engineering Applications in 2026

Imagine designing a high-pressure steam valve or a next-generation turbine blade, only to find that your flow calculations are off by 30% once the system hits operational speed. Why does the fluid suddenly behave like a solid wall? The culprit is likely a misunderstanding of the Mach Number. In the high-precision world of 2026 engineering, failing to account for the transition from incompressible to compressible flow isn’t just a calculation error—it is a recipe for structural failure. This guide breaks down the physics of velocity relative to sound, providing you with the exact formulas and regime classifications needed for modern fluid dynamics.

Key Takeaways

- Mach Number defines the ratio of an object’s velocity to the local speed of sound.

- Compressibility effects typically become significant at Mach Numbers greater than 0.3.

- The local speed of sound is highly dependent on temperature, not pressure.

Quick Definition

Mach Number (M) is a dimensionless quantity representing the ratio of the velocity of an object (or fluid flow) to the local speed of sound in that same medium. Mathematically expressed as M = u / c, it determines whether a flow is subsonic, transonic, supersonic, or hypersonic.

Founder’s Insight

“In my 20 years of plant commissioning, I’ve seen ‘choked flow’ destroy more control valves than corrosion ever could. Understanding the Mach Number at the valve throat is the difference between a silent system and a catastrophic vibration failure.”

— Atul Singla, Founder of Epcland

Table of Contents

Complete Course on

Piping Engineering

Check Now

Key Features

- 125+ Hours Content

- 500+ Recorded Lectures

- 20+ Years Exp.

- Lifetime Access

Coverage

- Codes & Standards

- Layouts & Design

- Material Eng.

- Stress Analysis

What is Mach Number and Why Does it Define Fluid Dynamics?

The Mach Number is more than just a measurement of speed; it is the fundamental indicator of how a fluid—be it air, steam, or natural gas—will react to an object moving through it. Named after the Austrian physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach, this dimensionless ratio serves as the gatekeeper between incompressible and compressible flow regimes. In 2026, as we push the boundaries of high-speed rail, aerospace propulsion, and industrial steam transport, mastering the Mach Number is critical for predicting shock waves and pressure distributions.

Physically, the Mach Number represents the ratio of inertial forces to elastic forces. When an object moves through a fluid, it creates pressure waves that travel at the speed of sound. If the object moves slower than these waves (Subsonic), the fluid “knows” the object is coming and moves out of the way. However, as the Mach Number approaches and exceeds 1.0, the object outpaces its own pressure signals, leading to the abrupt piling up of waves known as a shock wave.

The Critical Role: What is the Mach Number Used For in Industry?

In industrial engineering, the Mach Number is the primary diagnostic tool for system stability. Beyond the cockpit of a fighter jet, it is used extensively in the following 2026 applications:

- Control Valve Sizing: Engineers use the Mach Number to check for “Choked Flow” conditions where the flow rate reaches a maximum limit despite further pressure drops.

- Turbine Blade Design: High Mach Numbers at the tips of turbine blades can cause localized shock waves, leading to massive efficiency losses and vibrational fatigue.

- Natural Gas Pipelines: Monitoring the Mach Number ensures that flow velocities do not reach levels where friction and noise become ecologically and structurally damaging.

Understanding Compressibility and Mach Number Relationship

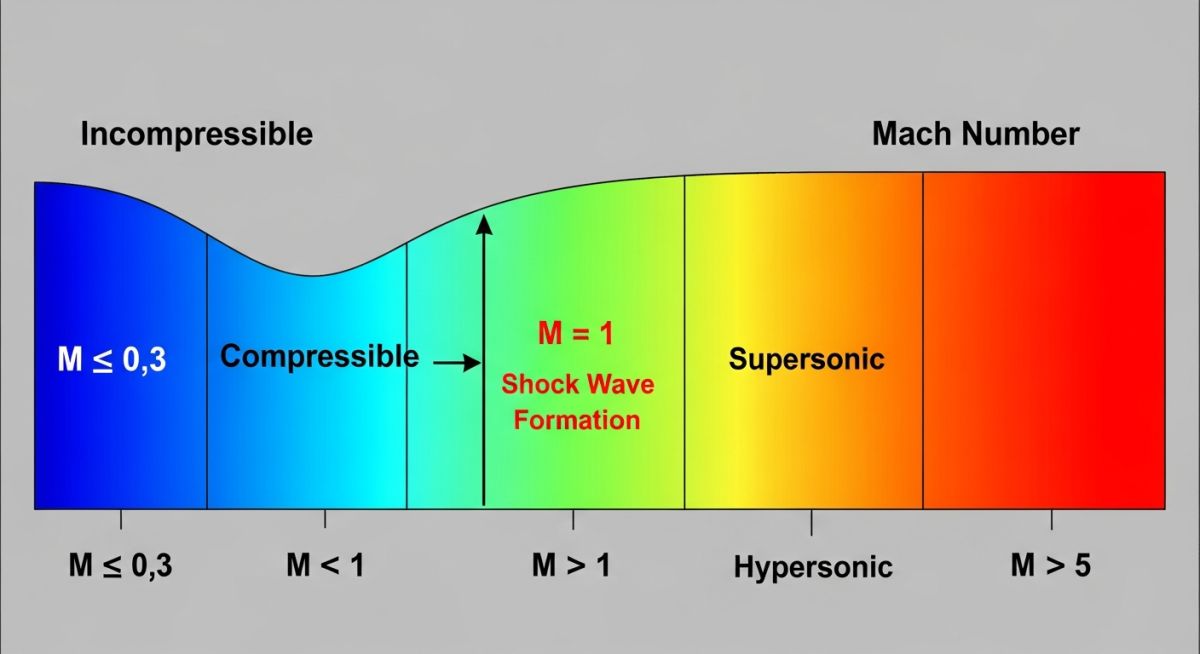

The transition from “incompressible” to “compressible” flow is the most vital threshold in fluid mechanics. For liquids and low-speed gases, we assume density is constant. However, as the Mach Number increases, the kinetic energy of the flow becomes high enough to physically compress the fluid molecules.

The standard engineering rule of thumb is that compressibility effects must be accounted for once the Mach Number exceeds 0.3. At this point, the density change in the fluid exceeds 5%, rendering Bernoulli’s traditional equation inaccurate. Engineers must then switch to the Compressible Bernoulli Equation or Isentropic flow relations to maintain safety margins.

Calculating Sonic Velocity: The Foundation of Mach Number

To determine the Mach Number, one must first accurately calculate the local speed of sound (c). In a perfect gas, the speed of sound is not a constant; it is a function of the medium’s thermodynamics.

Sonic Velocity Formula

c = √(γ R T)

Where:

- γ (Gamma): Ratio of specific heats (approx. 1.4 for air).

- R: Specific gas constant.

- T: Absolute temperature in Kelvin (the most critical variable).

Crucially, in 2026 high-altitude applications, engineers must remember that as an aircraft climbs, the temperature drops, which lowers the speed of sound. This means that a plane traveling at a constant physical speed (u) will see its Mach Number increase as it gains altitude.

Deriving the Formula for Mach Number

The mathematical derivation of the Mach Number is deceptively simple, yet it represents the balance of kinetic energy and internal energy within a moving fluid. In 2026, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) software still relies on this fundamental ratio to set boundary conditions for high-speed simulations.

The Basic Mach Formula

M = u / c

For advanced aerospace applications, we integrate the sonic velocity equation c = √(γRT) into the primary ratio to yield the full thermodynamic expression:

M = u / √(γRT)

Engineering Classification: The Importance of Mach Number Regimes

Engineers categorize flow based on the Mach Number because the governing equations change fundamentally at each boundary. Below is the standardized classification used in 2026 for mechanical and aerospace design:

| Flow Regime | Mach Range | Physical Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Subsonic | M < 0.8 | Streamlines are smooth. Density changes are negligible below M=0.3. |

| Transonic | 0.8 ≤ M ≤ 1.2 | Mixed flow; localized shock waves appear on curved surfaces. |

| Supersonic | 1.2 < M < 5.0 | Shock waves are prevalent. Information only travels downstream. |

| Hypersonic | M ≥ 5.0 | High thermal loads; ionization and chemical dissociation of air occurs. |

Mach Number and Flow Through Nozzles: The Area-Velocity Relationship

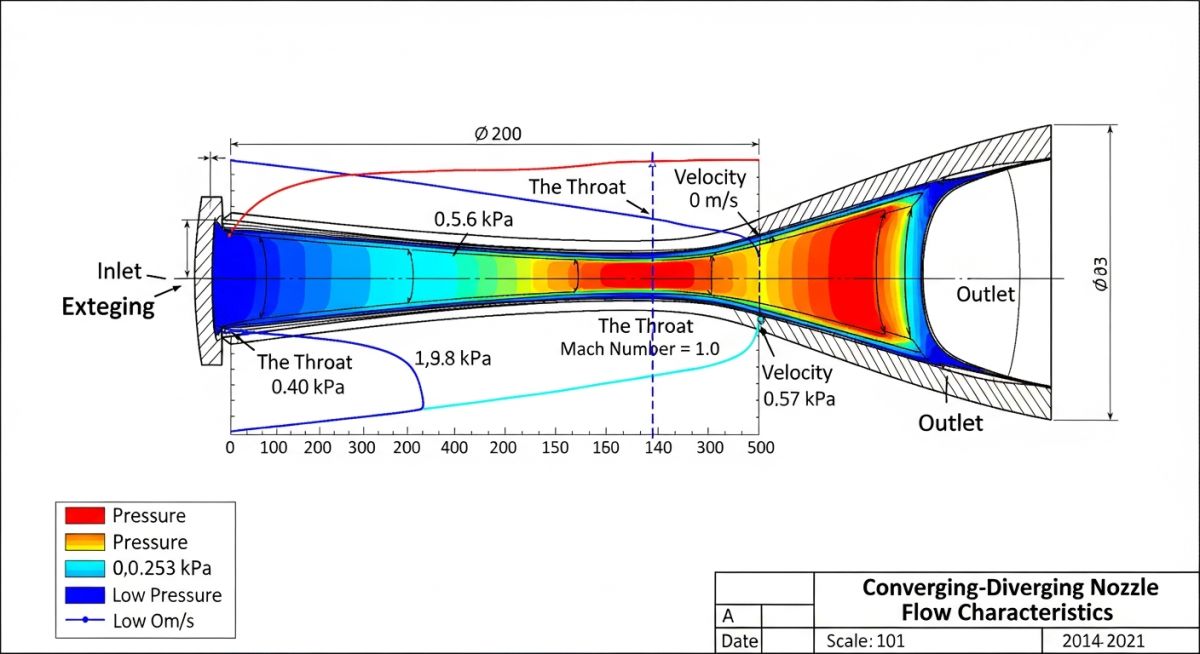

One of the most profound applications of the Mach Number is in the design of nozzles for rockets and steam turbines. The relationship between cross-sectional area (A) and velocity (u) is dictated by the Area-Velocity equation:

This equation reveals a counter-intuitive truth in fluid mechanics:

- In Subsonic Flow (M < 1): To increase velocity, you must decrease the area (Converging).

- In Supersonic Flow (M > 1): To increase velocity, you must increase the area (Diverging).

This is why supersonic nozzles are “hourglass” shaped (Converging-Diverging). At the narrowest point, known as the throat, the Mach Number is exactly 1.0.

2026 Industry Standards Compliance

All Mach-related calculations for pressurized piping systems should align with ASME B31.3 (Process Piping) for velocity limits and API 520/521 for pressure-relieving systems, specifically regarding high-velocity discharge and sonic choking thresholds.

2026 Engineering: Mach Number & Sonic Velocity Calculator

Sonic Velocity (c)

340.29 m/s

Mach Number (M)

0.999

Flow Regime

Transonic

Calculation assumes Ideal Gas (Air) where γ = 1.4 and R = 287 J/kg·K.

EPCLand YouTube Channel

2,500+ Videos • Daily Updates

Mach Number Failure Case Study: The "Choked Flow" Valve Vibration

The Scenario

In a high-pressure steam bypass station commissioned in late 2025, operators reported extreme acoustic vibration (exceeding 110 dB) and rapid downstream pipe thinning. The system was designed for a specific mass flow, but as the downstream pressure was lowered to increase throughput, the noise became deafening and structural supports began to crack.

The Mach Number Investigation

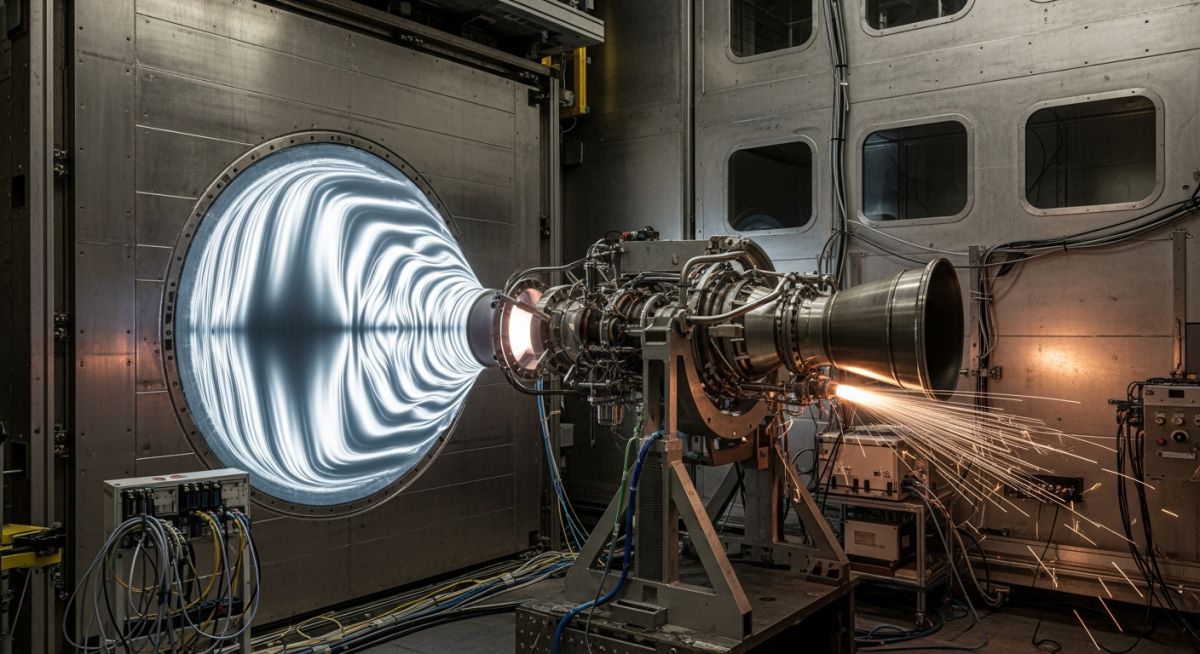

Engineering analysis revealed that the Mach Number at the valve trim had reached M = 1.0. This "Choked Flow" condition meant that the steam had reached sonic velocity at the narrowest restriction. When the steam exited this restriction into the larger downstream pipe, it underwent rapid supersonic expansion, creating a series of "shock diamonds."

These shock waves were not just acoustic nuisances; they were physically hammering the pipe walls. Because the designers had focused only on pressure drop rather than the Mach Number at the exit flange, they failed to realize the flow had transitioned into a destructive supersonic regime.

The Solution & Lesson

The valve was replaced with a multi-stage pressure reducing trim designed to keep the Mach Number below 0.3 at each stage. Lesson: Always verify the Mach Number at the valve exit and downstream piping. In 2026, exceeding M = 0.5 in steam service is considered a high-risk design that requires specialized acoustic insulation and heavy-wall piping.

Expert Insights: Lessons from 20 Years in the Field

- Temperature is the Driver: In industrial gas systems, never assume a constant Mach Number if your process has temperature swings. A 50°C increase in gas temperature significantly raises the sonic velocity, which actually lowers your Mach Number for the same physical flow rate.

- The M = 0.3 Rule: Always treat M = 0.3 as the "Incompressible Boundary." If your pipe sizing calculations show a Mach Number of 0.35, the standard Darcy-Weisbach equations start to lose accuracy. Switch to compressible flow models to avoid underestimating pressure drops.

- Material Fatigue: High Mach Number flows (M > 0.6) in piping systems create high-frequency vibrations. Ensure your pipe supports are designed for Acoustically Induced Vibration (AIV), a common failure point in 2026 high-pressure relief systems.

Frequently Asked Questions: Mach Number & Flow Dynamics

1. What Mach Number is considered supersonic?

2. At what speed does air become compressible?

3. Why is Mach Number used at high altitudes instead of knots?

4. Does pressure affect the Mach Number?

5. Can anything go Mach 10 in 2026?

6. Which Mach Number is considered the "beginning" of compressibility?

📚 Recommended Resources: Piping Engineering

Read these Guides

🎓 Advanced Training