Pitting Corrosion: The “Stealth Killer” of Piping Systems

Pitting Corrosion is widely regarded by integrity engineers as one of the most destructive and insidious forms of material degradation because it causes equipment failure with very little overall weight loss. Unlike general corrosion, which thins a pipe uniformly, pitting attacks extremely small areas, drilling deep holes that can lead to rapid perforation and leaks in high-pressure systems.

Technical Definition

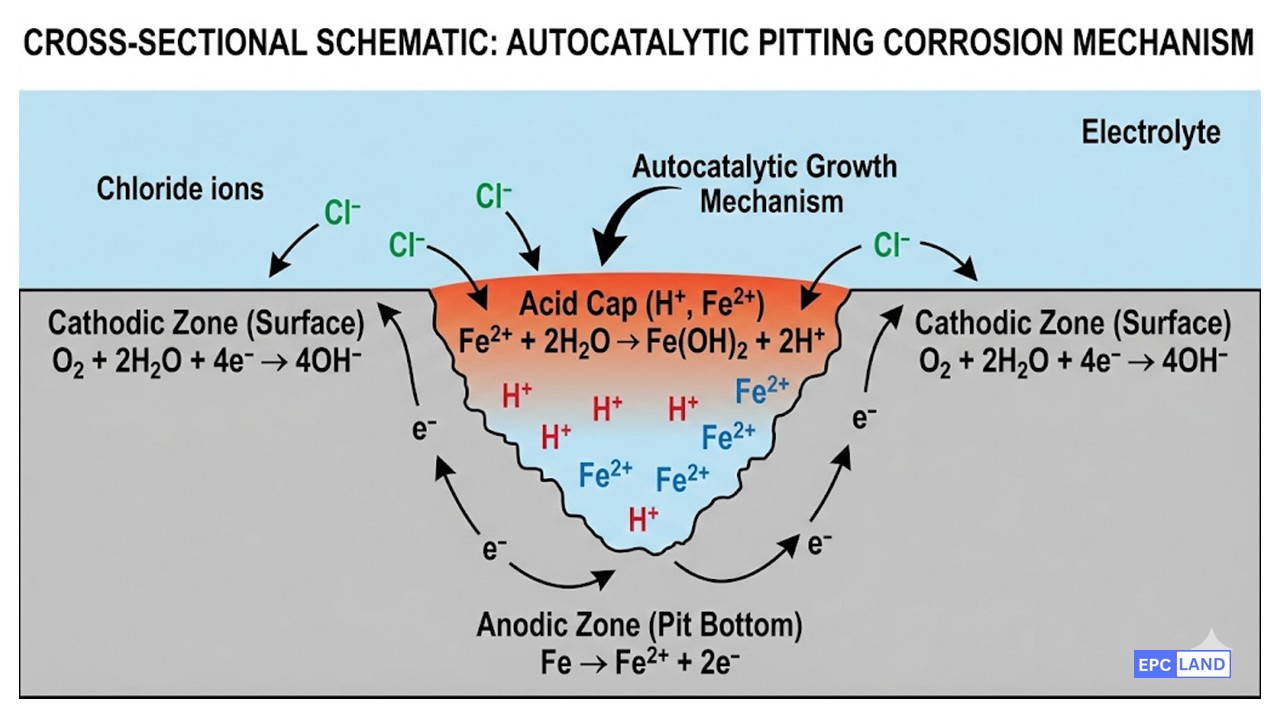

Pitting is a localized form of corrosion where cavities (pits) are produced in the material. It occurs when the protective passive film (oxide layer) on a metal surface breaks down in the presence of aggressive anions, most commonly Chlorides (Cl⁻). The resulting pit becomes anodic, while the surrounding surface remains cathodic, creating a self-sustaining “autocatalytic” reaction.

Quick Navigation

Test Your Metallurgy Knowledge

Question 1 of 5Loading…

💡 Explanation:

Complete Course on

Piping Engineering

Check Now

Key Features

- 125+ Hours Content

- 500+ Recorded Lectures

- 20+ Years Exp.

- Lifetime Access

Coverage

- Codes & Standards

- Layouts & Design

- Material Eng.

- Stress Analysis

The Electrochemical Mechanism

To prevent Pitting Corrosion, one must first understand why it happens. Stainless steels rely on a thin, invisible “passive” layer of Chromium Oxide (Cr₂O₃) for protection. However, this layer is not invincible.

The process begins with Passive Film Breakdown. In the presence of aggressive ions—specifically Chloride-Induced Corrosion agents found in seawater or process fluids—the oxide layer is locally breached. This creates a tiny electrical circuit. The exposed metal at the breach becomes the “Anode” (where metal dissolves), while the vast surrounding passive surface becomes the “Cathode.” Because the cathode area is huge compared to the tiny anode, the corrosion current density at the pit bottom is massive, drilling into the metal at accelerated rates.

Calculating Material Resistance (PREN)

Engineers use a theoretical ranking system called the Pitting Resistance Equivalent Number (PREN) to compare how different alloys withstand pitting. The formula emphasizes the role of Molybdenum (Mo) and Nitrogen (N) in strengthening the passive layer.

⚡ Engineering Formula: PREN

The standard formula for Austenitic and Duplex Stainless Steels is:

Variable Definitions:

- %Cr = Chromium Content

- %Mo = Molybdenum Content

- %N = Nitrogen Content

Rule of Thumb: For seawater service, a PREN > 40 is typically required (e.g., Super Duplex). Standard 316L (PREN ~24) will fail in seawater.

Alloy Comparison Matrix

The table below highlights why upgrading materials is often the most effective strategy against Pitting Corrosion. Note the jump in PREN values for Duplex grades.

| Common Name | UNS Grade | Typical PREN | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SS 304 | S30400 | 18 – 20 | Fresh water, architectural (Indoor) |

| SS 316L | S31603 | 23 – 25 | Marine atmosphere, potable water |

| Duplex 2205 | S31803 | 34 – 36 | Brackish water, chemical processing |

| Super Duplex | S32750 | > 41 | Seawater immersion, Offshore Oil & Gas |

Critical Pitting Temperature (CPT)

While PREN covers chemistry, temperature is the activation switch. The Critical Pitting Temperature (CPT) is the lowest temperature at which stable pitting occurs. For example, in 6% Ferric Chloride (ASTM G48 Test), SS 316 might pit at 15°C, while Super Duplex survives up to 80°C. Operating below the CPT is a key design constraint.

Case Study: Heat Exchanger Tube Perforation

Asset Type

Shell & Tube Heat Exchanger (CW Cooler)

Material Spec

Austenitic Stainless Steel (AISI 304)

Fluid Medium

Cooling Water (Chlorides: 600 ppm)

Time to Failure

18 Months (Unexpected Leakage)

The Failure Scenario

An onshore petrochemical facility experienced a sudden loss of containment in a cooling water heat exchanger. The unit utilized AISI 304 Stainless Steel tubes. The cooling water source was brackish, with chloride levels fluctuating between 400 and 800 ppm. Additionally, the unit had been left stagnant with water inside for 4 weeks during a partial turnaround.

Root Cause Analysis: The failure was attributed to Pitting Corrosion driven by two factors:

1. Material Limit: SS 304 (PREN ~18) is generally not recommended for waters with >200 ppm chlorides above 50°C.

2. Stagnation: Low flow conditions allowed suspended solids to settle on the tube walls. These deposits created “Differential Aeration Cells,” depriving the metal underneath of oxygen and preventing the repair of the passive oxide layer.

Engineering Solution & Testing

To permanently resolve the integrity threat, the Maintenance & Reliability team took the following steps:

- Material Upgrade: The tube bundle was retubed using Duplex 2205 (UNS S31803). With a PREN of ~35, it offers vastly superior resistance to localized chloride attack compared to SS 304.

- QA/QC Verification: The new material was subject to the ASTM G48 Test Method (Method A). This standard practice involves immersing samples in a ferric chloride solution to verify the Critical Pitting Temperature (CPT) meets the design requirement (>50°C).

- Operational Protocol: Procedures were updated to ensure heat exchangers are drained and dried if taken offline for more than 72 hours to prevent stagnant conditions.

💰 Operational Impact

The upgrade to Duplex 2205 cost approximately 2.5x the price of the original SS 304 bundle. However, the estimated service life increased from 1.5 years to 20+ years. By eliminating unscheduled shutdowns, the plant saved an estimated $450,000 in lost production revenue within the first 3 years of operation.

EPCLand YouTube Channel

2,500+ Videos • Daily Updates

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is Pitting Corrosion difficult to detect visually?

Pits are often covered by corrosion products (rust caps) or hidden under deposits. On the surface, the damage may look like a tiny pinprick or roughness, while the subsurface cavity is extensive. Specialized NDT methods like Eddy Current Testing (ECT) or Ultrasonic testing are often required for confident detection.

Can Cathodic Protection prevent Pitting?

Yes. Cathodic Protection works by lowering the potential of the metal surface below its “pitting potential” ($E_{pit}$). By supplying electrons to the metal (making it a cathode), the anodic dissolution reactions that drive pit growth are effectively suppressed, even in chloride-rich environments.

What is the difference between Pitting and Crevice Corrosion?

While the mechanism is similar (localized attack), the initiation differs. Pitting occurs on open, bold surfaces due to passive film breakdown. Crevice corrosion occurs in confined spaces (gaps under gaskets, bolt heads) where stagnant solution becomes acidic. Generally, a material’s resistance to crevice corrosion is lower than its resistance to pitting.

Can you repair a pipe damaged by pitting?

It depends on the depth. Shallow pits might be ground out if the remaining wall thickness meets code requirements. However, because pitting is “stochastic” (random) and deep, section replacement is usually the safest engineering choice. Weld repairs can introduce new stresses and sensitization, leading to recurring issues.

Summary: Winning the War on Pitting

Pitting Corrosion remains a primary threat to asset integrity in 2026, particularly in offshore and chemical processing sectors. The key to prevention lies not in hope, but in calculation. By utilizing the PREN formula, conducting ASTM G48 testing, and understanding the environmental limits (Chloride/Temperature), engineers can design systems that remain robust for decades.