The Ultimate Guide to Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) and Upper Explosive Limit (UEL): Safety, Monitoring, and Optimization

A worker stares at his gas monitor inside a storage vessel. It reads “0% LEL,” but there is a strange, thick smell of hydrocarbons in the air. He assumes he’s safe. What he doesn’t realize is that the concentration might be so high—so far above the Upper Explosive Limit (UEL)—that the sensor is “blinded.” The moment he opens the hatch and introduces fresh air, the mixture will drop back into the explosive range, turning the vessel into a bomb.

In industrial process safety, understanding the Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) and Upper Explosive Limit (UEL) is not just a regulatory requirement; it is the line between a routine shift and a catastrophic vapor cloud explosion. This guide explores the chemistry of flammability, the mechanics of detection, and the critical conversions needed to keep your facility safe.

Key Takeaways

- Define the “Flammable Range” and why concentrations outside this window won’t ignite.

- Master the conversion between %LEL and PPM (Parts Per Million).

- Understand why “Too Rich” (Above UEL) is often more dangerous than “Too Lean.”

What are LEL and UEL?

The Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) is the minimum concentration of a gas or vapor in air that can produce a flash of fire in the presence of an ignition source. The Upper Explosive Limit (UEL) is the maximum concentration. Between these two points lies the “Explosive Range” or “Flammable Range.”

“I’ve investigated several ‘mystery’ fires where the gas detector read zero just minutes before ignition. In 90% of those cases, the team failed to account for Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) and Upper Explosive Limit (UEL) dynamics during purging. If you don’t respect the flammability envelope, the physics of combustion will eventually catch up to you.”

— Atul Singla, Founder of Epcland

Table of Contents

- 1. Understanding the Flammability Range: LEL and UEL

- 2. Defining the Minimum Threshold: What is the LEL?

- 3. The “Too Rich” Zone: What is the UEL?

- 4. Industrial Significance of LEL and UEL in Process Safety

- 5. LEL and UEL of Various Fuels (Gases/Vapors)

- 6. Advanced Detection: LEL Sensors and Portable Meters

- 7. The Math of Safety: How to Convert %LEL to PPM

- 8. Case Study: The Vapor Cloud Ignition

- 9. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Complete Course on

Piping Engineering

Check Now

Key Features

- 125+ Hours Content

- 500+ Recorded Lectures

- 20+ Years Exp.

- Lifetime Access

Coverage

- Codes & Standards

- Layouts & Design

- Material Eng.

- Stress Analysis

Safety Verification Quiz

Validate your knowledge of explosive atmospheres before proceeding.

1. If a gas concentration is measured at 2% by volume, but its Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) is 5%, what is the state of the atmosphere?

Understanding the Flammability Range: What are Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) and Upper Explosive Limit (UEL)?

To understand the Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) and Upper Explosive Limit (UEL), we must first look at the chemistry of combustion. For a fire or explosion to occur, three elements must be present in the correct proportions: fuel (in the form of gas or vapor), an oxidizer (usually the oxygen in the air), and an ignition source (heat, spark, or flame). However, simply having fuel and oxygen together is not enough to guarantee an explosion. The mixture must fall within a specific concentration window known as the Flammable Range or Explosive Range.

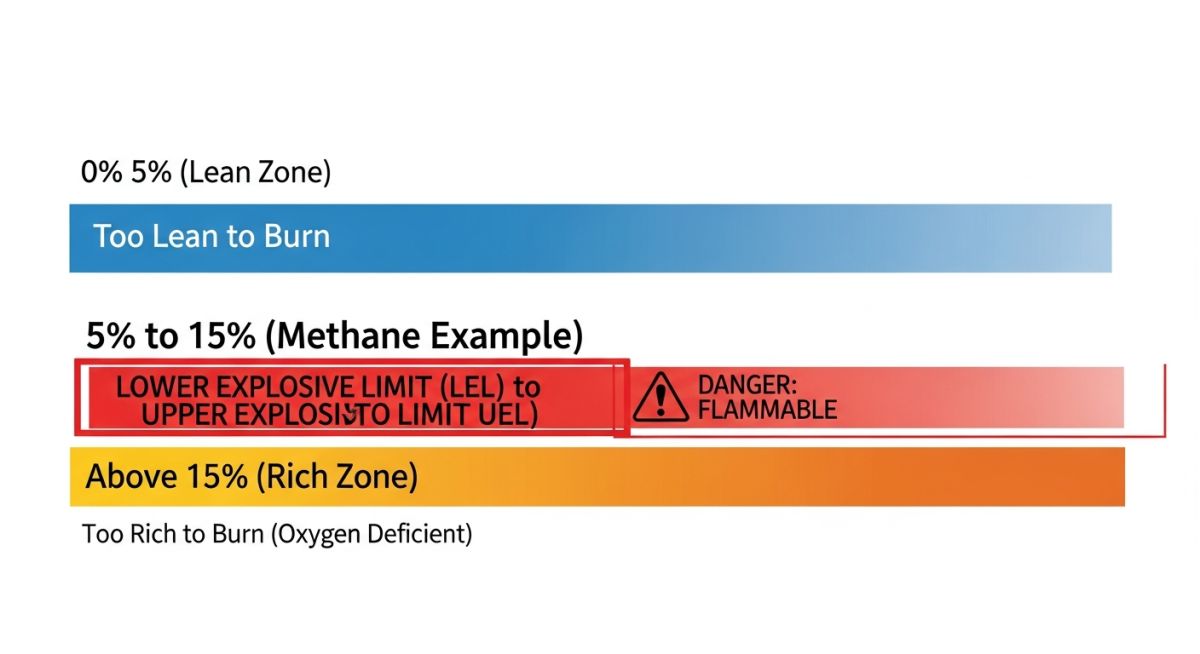

This range is defined by two critical points. If the concentration of gas is below the Lower Explosive Limit (LEL), the mixture is considered “Too Lean”—there is simply not enough fuel to support a continuous flame front. Conversely, if the concentration is above the Upper Explosive Limit (UEL), the mixture is “Too Rich”—there is so much fuel that it has displaced the oxygen necessary for combustion to propagate. This fundamental concept is the cornerstone of Hazardous Area Classification (ATEX/IECEx) and process safety management.

Figure 1: The Flammability Spectrum and the Dangerous “Explosive Zone” between LEL and UEL.

Defining the Minimum Threshold: What is the Lower Explosive Limit (LEL)?

The Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) is the lowest concentration (by percentage volume) of a gas or vapor in air that is capable of producing a flash of fire in the presence of an ignition source. For example, the LEL of Methane is 5% by volume. This means that in any room or vessel, if the methane concentration is less than 5%, it cannot explode, even if you introduce an open flame.

In industrial monitoring, we rarely wait for the gas to reach 100% of its LEL. Instead, gas detectors are calibrated to show % LEL. A reading of “50% LEL” for Methane does not mean the air is 50% gas; it means the air has reached 50% of the threshold required for an explosion. In this case, 50% of 5% equals a 2.5% actual concentration of Methane in the air. Most safety protocols (OSHA and NFPA) require evacuation or automated shutdown when levels reach 10% to 25% LEL to provide a massive factor of safety.

The “Too Rich” Zone: What is the Upper Explosive Limit (UEL)?

The Upper Explosive Limit (UEL) represents the highest concentration of a gas or vapor in air that will burn or explode. Above this point, the mixture is too “fuel-rich” to ignite because the fuel has displaced the oxygen to a level where the chemical reaction cannot be sustained. While an atmosphere above the UEL might seem “safe” because it won’t explode, it is often more dangerous than a lean environment for two reasons:

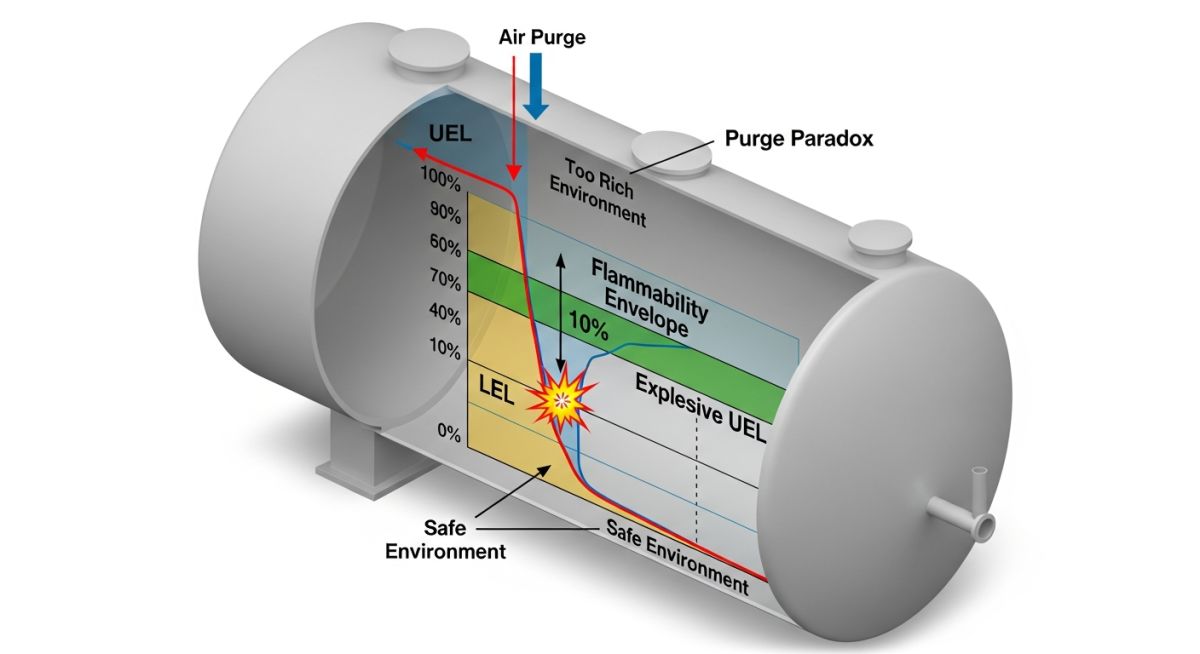

- The Purge Risk: If you have a tank filled with gas at a concentration above the UEL and you open it to the atmosphere, the incoming fresh air will dilute the mixture. This dilution forces the concentration to drop directly through the explosive range before it becomes lean and safe.

- Oxygen Deficiency: Any atmosphere above the UEL is likely to be Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health (IDLH) due to oxygen displacement, leading to rapid asphyxiation for anyone entering without a supplied-air respirator.

Industrial Significance of Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) and Upper Explosive Limit (UEL)

In the engineering of oil refineries, chemical plants, and wastewater treatment facilities, the Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) and Upper Explosive Limit (UEL) dictate the design of ventilation systems and the selection of electrical equipment. NFPA 69 (Standard on Explosion Prevention Systems) utilizes these limits to determine “Inerting” requirements—adding nitrogen or carbon dioxide to a vessel to keep the oxygen levels so low that the explosive range is physically impossible to reach, regardless of the fuel concentration.

Engineering Data: Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) and Upper Explosive Limit (UEL) of Various Fuels

Every hydrocarbon and flammable gas has a unique chemical signature that determines its flammability envelope. As a process engineer, having these values on hand is critical for calculating purge times and setting alarm thresholds on Fixed Gas Detection Systems. Below is a reference table for the most common industrial gases tested at standard atmospheric conditions.

| Gas / Vapor | LEL (% by Vol) | UEL (% by Vol) | Flash Point (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methane (CH4) | 5.0% | 15.0% | Gas |

| Propane (C3H8) | 2.1% | 9.5% | Gas |

| Hydrogen (H2) | 4.0% | 75.0% | Gas |

| Acetylene (C2H2) | 2.5% | 100.0% | Gas |

| Gasoline (Vapor) | 1.4% | 7.6% | -43°C |

| Ethanol | 3.3% | 19.0% | 13°C |

Advanced Detection Technology: LEL Sensors and Portable Gas Meters

Detecting the Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) and Upper Explosive Limit (UEL) in a real-world plant environment requires specialized sensor technology. Not all sensors are created equal, and choosing the wrong one can lead to a false sense of security.

Catalytic Bead (Pellistor)

The most common LEL sensor. It works by burning a small amount of gas on a heated coil. The resulting temperature change is measured as a change in resistance.

- Detects almost all flammable gases including Hydrogen.

- Risk: Can be “poisoned” by silicones, lead, or sulfur.

- Requires oxygen to operate.

Non-Dispersive Infrared (NDIR)

Uses infrared light to measure the absorption of gas molecules. Each gas absorbs light at a specific wavelength.

- Cannot be poisoned; very high stability.

- Does not require oxygen to operate (ideal for inerting).

- Risk: Cannot detect Hydrogen or Acetylene.

Understanding Concentration: What are PPM and PPB in Gas Detection?

While the Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) and Upper Explosive Limit (UEL) are measured in percentages of volume, many toxic gases or trace leaks are measured in Parts Per Million (PPM) or Parts Per Billion (PPB).

Think of it this way: 1% of the atmosphere is equal to 10,000 PPM. Therefore, a gas like Methane, which has an LEL of 5.0%, actually has an LEL of 50,000 PPM.

Concentration Scale Reference

Why does this matter? Many gases are toxic long before they become explosive. For instance, Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S) has an LEL of 4.0% (40,000 PPM), but its toxicity threshold (OSHA PEL) is only 10 PPM. If you only monitor for %LEL, you could be killed by toxicity while the meter still reads “0% LEL.”

Safety Conversion: % LEL to PPM Calculator

Convert your gas detector’s % LEL reading into PPM (Parts Per Million) and Actual Volume %. This is critical for understanding the true concentration of a leak.

* Example: 10% LEL is a common low-alarm setpoint.

Safety Note: Most gas detectors display 0-100% of the LEL, not the total volume of air. Always know your gas type!

Gas Concentration in Air

Parts Per Million

EPCLand YouTube Channel

2,500+ Videos • Daily Updates

Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) and Upper Explosive Limit (UEL) Failure Case Study: The Purging Paradox

The Problem: A “Safe” Tank Explodes

During a routine maintenance shutdown at a chemical storage terminal, a large tank that had previously held high-purity Ethane was scheduled for internal inspection. The tank atmosphere was measured and found to be at 85% Ethane by volume. Since the Upper Explosive Limit (UEL) for Ethane is approximately 12.4%, the safety team correctly identified that the mixture was “too rich” to burn.

The crew began a high-speed air-purging process to vent the tank before entry. However, thirty minutes into the purging, a catastrophic explosion occurred, lifting the tank roof and causing severe damage to the surrounding piping.

The Root Cause Analysis

The investigation revealed that the team failed to account for the “transition zone” between the Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) and Upper Explosive Limit (UEL). By using fresh air to purge a fuel-rich environment, they were essentially diluting the mixture from 85% (Above UEL) down to 0%.

Technical Findings:

- The Flammable Window: As air entered, the concentration dropped from 85% to 3%. In doing so, the mixture spent nearly 10 minutes within the flammable range (3.0% LEL to 12.4% UEL).

- Ignition Source: Static electricity, generated by the high-velocity air rushing through the nozzle, provided the spark necessary to ignite the now-explosive atmosphere.

- The Oxygen Factor: While the mixture was above the UEL, it lacked the oxygen to ignite. The purging process provided the missing oxidizer.

The Resolution & Safe Protocol

To prevent such incidents, industry standards like NFPA 69 mandate a “Double Purge” or “Inert Purge” protocol:

- Step 1: Purge the vessel with Nitrogen (an inert gas) until the fuel concentration is below the “Limiting Oxygen Concentration” (LOC) or well below the LEL.

- Step 2: Once the flammable gas is removed, introduce air for ventilation. This ensures the mixture never crosses into the flammable region.

Lessons Learned:

Operating above the Upper Explosive Limit (UEL) is not a safety strategy—it is a temporary state of instability. Always use inert media to transition through the explosive range during decommissioning or maintenance.

Expert Insights: Lessons from 20 years in Hazardous Area Safety

Managing Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) and Upper Explosive Limit (UEL) risks requires moving beyond the datasheet. Here are the hard-won lessons from the field:

- ● The Temperature Trap: LEL values are not static. As the ambient temperature increases, the Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) decreases. In a hot furnace or reactor environment, a gas that is “safe” at 20°C may become explosive at 100°C because the molecules already possess higher kinetic energy.

- ● The Catalytic “Blind Spot”: Catalytic bead sensors (Pellistors) require oxygen to work. If you are monitoring a vessel that has been nitrogen-purged and is above the Upper Explosive Limit (UEL), your sensor may read “0% LEL” or fail completely because there isn’t enough oxygen to burn the gas on the bead. Always use Infrared (IR) sensors for inert environments.

- ● Dust is the Forgotten Fuel: Don’t just look for gases. In many industrial settings, the Minimum Explosible Concentration (MEC) for dust acts like an LEL. If you have fine powders (sugar, flour, coal), they can explode long before any gas detector triggers an alarm.

- ● Cross-Sensitivity Risks: A detector calibrated for Methane will give an inaccurate reading for Propane or Butane. Always use the “K-Factor” (Response Factor) provided by the manufacturer to correct your % LEL reading if the target gas differs from the calibration gas.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between LEL and UEL?

What is a typical LEL for Methane?

What does the “Flammable Range” mean?

Why is a “0% LEL” reading on a gas monitor sometimes a lie?

How can a gas concentration be above the UEL but still ignite?

Why do some industries use 10% LEL as an alarm while others use 25% LEL?