What is Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC)? Mechanism and Prevention of SCC

Core Takeaways

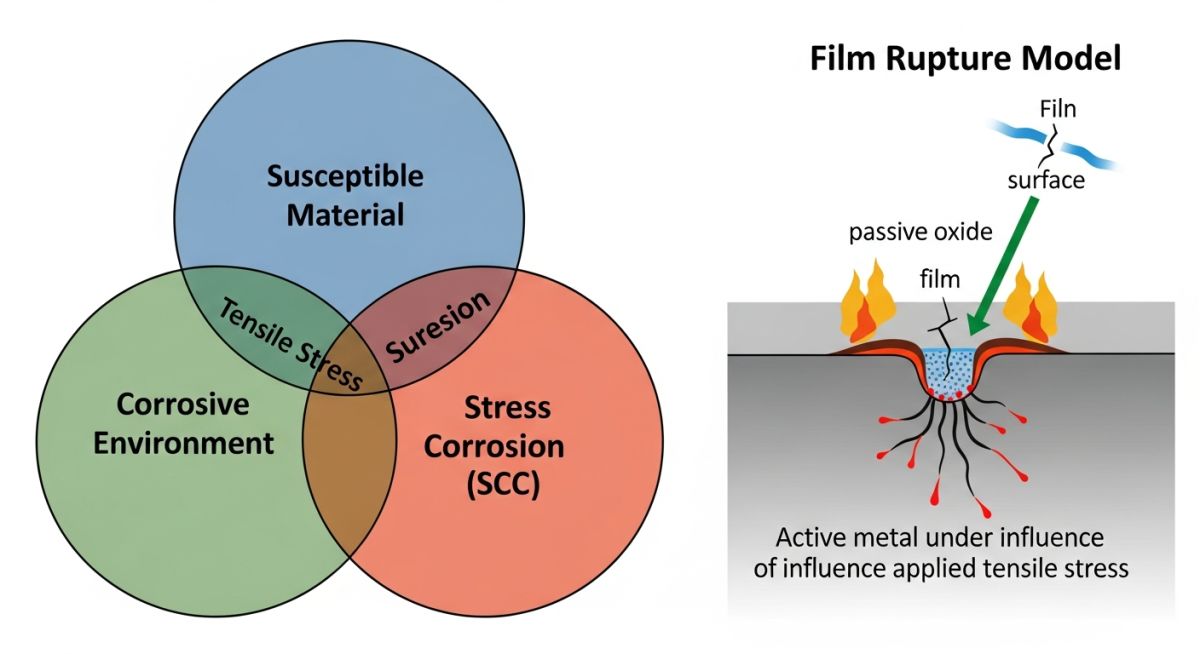

- The SCC Trinity: Failure only occurs when a susceptible material, a specific corrosive environment, and tensile stress intersect.

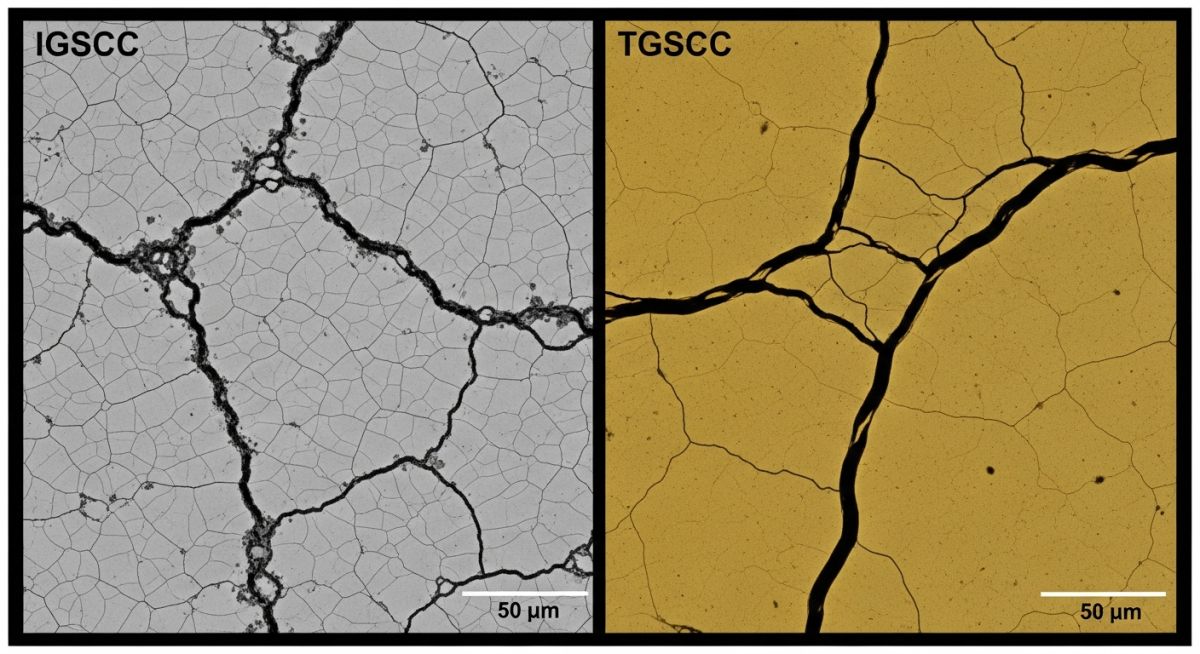

- Crack Morphology: SCC is uniquely characterized by fine, branching cracks that can be either intergranular or transgranular.

- Prevention Hierarchy: Material selection and residual stress relief (SRHT) are more effective than simple coatings.

What is Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC)?

Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) is a failure mechanism characterized by the growth of cracks in a corrosive environment under constant tensile stress. It is a synergistic process where the combination of environment and stress causes catastrophic brittle failure in otherwise ductile metals, often without significant visible corrosion.

“In my 20 years of plant inspections, the most dangerous SCC cases were those hidden under insulation. Engineers often forget that residual stress from cold working or welding is just as lethal as operational pressure. Never underestimate the chemistry of seemingly ‘mild’ environments.”

— Atul Singla

Article Navigation

- What Causes Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC)?

- Common Types of Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC)

- Characteristic Features of Stress Corrosion Cracking

- Engineering Materials Susceptible to SCC

- Impact of SCC in Welding Operations

- Investigating the Mechanisms of SCC

- Practical Strategies to Prevent SCC

- Expert Summary on SCC Failures

Complete Course on

Piping Engineering

Check Now

Key Features

- 125+ Hours Content

- 500+ Recorded Lectures

- 20+ Years Exp.

- Lifetime Access

Coverage

- Codes & Standards

- Layouts & Design

- Material Eng.

- Stress Analysis

Knowledge Check: SCC Engineering Mastery

Test your understanding of Stress Corrosion Cracking mechanisms.

Which three factors must coexist for Stress Corrosion Cracking to occur?

What Causes Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC)?

The occurrence of Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) is never accidental; it is a calculated failure that requires the simultaneous presence of three specific conditions, often referred to as the SCC Trinity. According to the NACE MR0175/ISO 15156 standard, these factors are a susceptible material, a specific corrosive environment, and tensile stress. If any one of these elements is removed, the cracking process ceases entirely.

Tensile stress is the mechanical driver, which can be either applied (operational pressure) or residual (internal stresses from welding, cold working, or thermal cycles). In many industrial failures, the residual stress from fabrication alone exceeds the threshold required to initiate cracks. The environment must contain specific chemical species—such as chlorides for stainless steels or ammonia for copper alloys—that interact with the metal's surface to facilitate localized attack rather than general wastage.

Common Types of Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC)

SCC is categorized based on the environment-metal pairing and the resulting crack morphology. The most prevalent industrial types include:

- Chloride SCC (Cl-SCC): Affects austenitic stainless steels (300 series) in environments containing moisture and chlorides, particularly at temperatures above 60°C (140°F).

- Sulfide Stress Cracking (SSC): A specific form of hydrogen-induced SCC occurring in "sour" service (H2S environments) common in oil and gas production, as defined by ISO 15156-1.

- Caustic Embrittlement: Cracking of carbon steels and nickel alloys in highly alkaline environments, often found in steam boiler systems.

- Ammonia SCC: Historically known as "season cracking" in brass, where atmospheric moisture and ammonia trace amounts lead to intergranular failure.

Characteristic Features of Stress Corrosion Cracking

Identifying Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) requires an understanding of its unique fracture mechanics. Unlike fatigue or ductile overload, SCC exhibits brittle-like failure in materials that are otherwise highly ductile. The cracks typically propagate perpendicular to the direction of the tensile stress and are characterized by a highly branched, "river-like" pattern.

Microscopically, the cracks may follow grain boundaries (Intergranular SCC) or cut across the grains (Transgranular SCC), depending on the alloy composition and environmental severity. Crucially, there is often zero visible macroscopic deformation; the component maintains its original dimensions until the remaining metal ligament can no longer support the load, leading to a sudden, catastrophic snap.

Engineering Materials Susceptible to Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC)

While almost all alloys have a "kryptonite" environment, certain materials are notorious for their SCC vulnerability in specific industrial settings. Designers must reference ASME Section II or equivalent tables to determine susceptibility ratings.

- Austenitic Stainless Steels: Grades like 304 and 316 are highly susceptible to Cl-SCC. Higher nickel and molybdenum content in 317L or Duplex grades (2205) provides improved resistance.

- High-Strength Steels: Steels with a yield strength exceeding 100 ksi are prone to hydrogen-assisted SCC, necessitating strict hardness controls (typically <22 HRC).

- Aluminum Alloys: 2000 and 7000 series alloys used in aerospace are vulnerable in marine atmospheres, often requiring specific over-aging heat treatments.

- Copper Alloys: Brass is highly sensitive to ammonia, even in concentrations as low as a few parts per million.

Impact of Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) in Welding Operations

Welding is the most significant contributor to Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) in industrial assets. The process introduces a lethal combination of altered metallurgy and high residual tensile stress. During the cooling cycle, the weld metal and the adjacent Heat-Affected Zone (HAZ) contract, creating localized stresses that often reach the yield strength of the base material. According to established API RP 571 damage mechanism protocols, these residual stresses are sufficient to drive cracking even in the absence of external operational loads.

Furthermore, "sensitization" during welding can precipitate chromium carbides at grain boundaries in stainless steels, depleting the surrounding areas of corrosion-resisting chromium. This makes the HAZ a prime target for intergranular SCC. To mitigate this, ASME B31.3 mandates strict controls on heat input and, in many corrosive services, requires mandatory Post-Weld Heat Treatment (PWHT) to relax these "locked-in" stresses.

Investigating the Mechanisms of Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC)

SCC is not a single-step event but a multi-stage progression. Engineering literature recognizes several distinct models to explain how cracks initiate and propagate in diverse environments:

Mechano-electrochemical Model

This model views SCC as a synergistic interaction where plastic deformation at the crack tip accelerates the local electrochemical dissolution of the metal, creating a self-sustaining cycle of growth.

Film Rupture Model

Most resistant alloys rely on a thin passive oxide film for protection. In this model, tensile stress causes local "slip" that ruptures this film, exposing fresh reactive metal to the environment. Rapid corrosion occurs at the break before the film can reform (repassivate), leading to a sharp crack.

Adsorption Phenomenon

Specific chemical species (like hydrogen or ions) adsorb onto the metal surface, weakening the atomic bonds at the crack tip. This reduces the energy required for the metal to fracture, facilitating crack advancement at stresses far below the normal fracture toughness.

Pre-existing Active Path Model

In this scenario, the material already contains "active paths" such as grain boundaries or segregated impurities that are more susceptible to corrosion. The stress simply acts to pull the corroded path apart, exposing deeper material to the environment.

| Environment | Susceptible Alloy | Primary Standard | Mitigation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorides (Cl-) | Austenitic SS (304/316) | API 571 | Material Substitution (Duplex) |

| Sour Service (H2S) | Carbon & Low Alloy Steel | ISO 15156 | Hardness Control (<22 HRC) |

| Caustic (NaOH) | Carbon Steel / Ni Alloys | ASME BPVC Sec VIII | Stress Relief (PWHT) |

| Ammonia (NH3) | Copper Alloys (Brass) | ASTM B154 | Stress Relief Annealing |

Practical Strategies to Prevent Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC)

Preventing SCC requires a proactive "Defense-in-Depth" strategy. Relying solely on one method is rarely sufficient for high-consequence assets. The 2026 engineering consensus emphasizes three primary pillars of prevention:

- Material Selection: Upgrading to alloys with higher resistance, such as high-nickel alloys (Inconel) or Duplex Stainless Steels (2205/2507), which possess a microstructure that resists crack propagation.

- Stress Mitigation: Utilizing Post-Weld Heat Treatment (PWHT) at a minimum of 1150°F (621°C) for carbon steel to relax residual stresses. Surface treatments like shot peening can also be used to introduce compressive stress, which effectively "squeezes" cracks shut.

- Environmental Control: Modifying the process chemistry to remove aggressive ions (e.g., chloride removal via ion exchange) or using corrosion inhibitors that reinforce the passive film on the metal surface.

SCC Risk Assessment Calculator (2026 Edition)

Evaluate the probability of Stress Corrosion Cracking based on material type, stress levels, and environmental chemistry.

Adjust the inputs to see the impact on SCC susceptibility.

EPCLand YouTube Channel

2,500+ Videos • Daily Updates

Engineering Case Study: Coastal Refinery Failure Analysis

The Asset

AISI 304 Stainless Steel Overhead Piping System (Uninsulated).

The Environment

Marine atmosphere with 450ppm Chloride concentration; Operating Temp 85°C.

The Failure

Sudden brittle fracture at a non-stress-relieved circumferential weld joint.

Root Cause Investigation

Post-failure analysis revealed that while the internal fluid was non-corrosive, the external coastal air deposited chlorides on the pipe surface. The operating temperature of 85°C caused local evaporation, concentrating the chlorides significantly. Metallographic cross-sections (shown above) confirmed Transgranular Stress Corrosion Cracking originating from the Heat Affected Zone (HAZ) of the weld.

2026 Rectification Strategy:

- Material Upgrade: Replaced the 304 series with Duplex Stainless Steel 2205 to utilize its superior chloride resistance.

- Surface Modification: Applied Shot Peening to the weld areas to induce a layer of protective compressive stress.

- Barrier Protection: Installed a specialized high-temperature aluminum foil wrap to prevent chloride-laden moisture from contacting the metal surface directly.

Expert Insights: Lessons from 20 years in the field

Beware of the "Idle" Asset: Most engineers focus on operating stresses, but SCC often accelerates during shutdowns. Hydrostatic test water left in stainless steel lines can concentrate chlorides as it evaporates, initiating pits that turn into SCC cracks once the system is pressurized.

Hardness is a Proxy for Risk: In sour service (H2S), hardness is your primary indicator. Keeping carbon steel below 22 HRC (Hardness Rockwell C) as per ISO 15156 is non-negotiable for preventing Sulfide Stress Cracking.

The Temperature Threshold Fallacy: While 60°C is the "standard" threshold for Chloride SCC, I have seen failures at 45°C in highly stressed thin-walled tubing. Always design for the worst-case chemistry, not just the temperature.

Frequently Asked Questions: Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC)

What is the difference between SCC and Fatigue? ▼

Can SCC occur at room temperature? ▼

Why is SCC called a "silent killer" in engineering? ▼

Does painting or coating a pipe guarantee protection against SCC? ▼

Why did my "Stress-Relieved" component still fail from SCC? ▼

Is it possible to "repair" a component affected by SCC? ▼