Grouting in Civil Construction: The Definitive Guide to Materials, Methods & Standards (2026)

The practice of Grouting in Civil Construction is a fundamental process involving the injection of pumpable material into soil, rock, or structural voids to improve their physical characteristics. This guide breaks down the essential standards, diverse materials, and advanced injection methods—from simple gravity flow to complex compensation techniques—required to ensure the long-term stability and integrity of critical infrastructure projects.

What is Grouting?

Grouting is a specialized construction technique where a fluid material, typically a cementitious or chemical mix, is pumped under pressure into a porous medium or fractured structure. The primary goal is to decrease permeability, increase load-bearing capacity, fill voids, or control ground water flow, providing structural stability and preventing settlement in geotechnical and foundational engineering works.

Test Your Grouting Knowledge (Interactive Quiz)

Complete Course on

Piping Engineering

Check Now

Key Features

- 125+ Hours Content

- 500+ Recorded Lectures

- 20+ Years Exp.

- Lifetime Access

Coverage

- Codes & Standards

- Layouts & Design

- Material Eng.

- Stress Analysis

The Fundamental Role and Purpose of Grouting in Engineering Projects

Grouting is indispensable in both new construction and remediation. Its core purpose extends beyond simply filling space; it is a meticulously planned engineering intervention designed to modify and enhance the physical properties of the subsurface or the structure itself. The decision to use a specific grout is based on the target medium (rock, soil, or concrete) and the desired outcome (permeability reduction, strength increase, or settlement control).

Key Benefits: Structural Repair, Sealing, and Soil Stabilization

The application of grouting addresses critical deficiencies across multiple engineering disciplines:

- Structural Void Filling: Grouting is essential for filling voids beneath foundations, within masonry, or in mass concrete to ensure uniform load transfer and prevent localized stress concentrations. This is a vital component of long-term Structural Repair work.

- Permeability Reduction (Sealing): In dam and tunnel construction, chemical or cementitious grouts are injected into fissured rock (e.g., in Curtain Grouting) to significantly reduce water flow, protecting the structure from hydraulic uplift and piping erosion.

- Soil Stabilization: Techniques like **Compaction Grouting** increase the density and shear strength of weak or loose soils, mitigating the risk of settlement under new loads, such as large bridges or industrial complexes.

ASME/API Standards Context for Grout Use

For heavy industrial and petrochemical applications, especially for grouting under baseplates of rotating machinery or compressors, adherence to standards like ASME B73.1M and practices outlined by **API Recommended Practice 686** is mandatory. These standards ensure that the grout provides:

- Non-Shrink Performance: Critical for maintaining the precise alignment and flatness required for machinery operation.

- High Early and Ultimate Compressive Strength: To withstand high static and dynamic loads without cracking.

- Chemical Resistance: Necessary in environments exposed to process fluids or aggressive chemicals.

Types of Grouting Materials: Cementitious, Chemical, and Polymer-Based

The type of grout material dictates the final performance and is selected based on the size of the voids/fissures, required strength, and permeability of the target zone. The three main classes are:

These are the most common, based on Portland cement, water, and often sand or pozzolanic materials. They are suitable for large voids (over 0.5 mm) and high-strength applications. Key variations include microfine cement for smaller fissures, and polymer-modified cement for improved adhesion and flexibility.

Used for injecting fine-grained soils or fissures (less than 0.1 mm) where cement particles cannot penetrate. Common types include acrylamide, acrylate, and polyurethane-based resins. They achieve significant reductions in permeability quickly, often setting into a rigid or flexible gel.

Mainly polyurethane, epoxy, and polyester resins. These are lightweight, high-strength materials used for structural crack injection and rapid sealing where extremely fast curing times and superior bond strength are needed. They are key in the most difficult **Grouting Procedures**.

Grout Characteristics: Flowability, Strength (G1 vs G2), and Setting Time

The success of a grouting operation hinges on matching the material's properties to the site conditions.

- Flowability (Viscosity): Measured by the Marsh Funnel test. Highly fluid grouts are necessary for permeating fine-grained soil or rock fissures (Permeation Grouting).

- Setting Time: Can range from seconds (for emergency water-stopping chemical grouts) to several hours (for large volume cementitious pours).

-

Strength (G1 vs G2): These are classifications, often related to specific project specifications, defining the minimum required compressive strength.

- G1 Grout: Typically refers to a standard, high-strength cementitious grout used for general structural purposes.

- G2 Grout: Denotes a superior, often non-shrink, extra high-strength grout (e.g., > 8,000 psi) reserved for high-precision applications like machinery baseplates where dynamic loads and precise alignment are critical.

Figure 1: Conceptual illustration of three primary grouting techniques for ground modification.

Strategic Grout Material Selection (LSI: Grout Material Selection)

The correct **Grout Material Selection** process follows a key decision tree based on two factors: the characteristics of the medium (porosity, void size) and the engineering goal (sealing vs. strengthening).

| Target Medium | Void/Fissure Size Range | Recommended Grout Type | Primary Engineering Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse Gravel/Rock Voids | > 0.5 mm | Cementitious (w/ Sand) | Void Filling & Structural Strength |

| Fine Sand/Fissured Rock | 0.05 mm - 0.5 mm | Microfine Cement / Silicate Chemical | Permeability Reduction |

| Very Fine Sand/Clayey Soil | < 0.05 mm | Acrylamide or Polyurethane Gel | Sealing & Waterproofing |

Detailed Grouting Procedures: The Step-by-Step Process (LSI: Grouting Procedures)

Executing successful grouting requires methodical planning and strict adherence to protocol. This encompasses preparation, mixing, application, and quality control, forming a critical chain in reliable **Grouting Procedures**.

Substrate Preparation and Mixing the Concrete Grout Mix (LSI: Concrete Grout Mix)

- Surface Cleaning: For structural grouting (e.g., column baseplates), the concrete substrate must be clean, sound, and free of oil, grease, or loose debris. Water blasting or light chipping is often required.

- Pre-Wetting: Non-absorbent surfaces prevent water loss from the grout. The area is typically saturated with water for 12-24 hours prior to application, but excess standing water must be removed before pouring.

- Mixing the Concrete Grout Mix: This must strictly follow manufacturer specifications. High-shear mixers are often used, especially for non-shrink grouts, to ensure proper dispersion and activation of the non-shrink and flow-enhancing additives. Improper mixing leads to reduced final strength.

- Formwork: Sealed, rigid formwork is installed to contain the grout and facilitate its flow. Head boxes are often used to ensure a positive pressure head to drive the grout into all voids.

Practical Guide to Tile Grout Application (LSI: Tile Grout Application)

While smaller scale, **Tile Grout Application** is an essential construction detail that impacts both aesthetics and structural integrity.

A rubber float for application, a sponge for cleaning, and a margin trowel for mixing are standard tools for residential and commercial tile grouting projects.

The grout is spread over the tiles, forcing the mix into the joints using the float. Excess grout is scraped off immediately, and the joints are 'struck' (shaped) and cleaned with a damp sponge after an initial set period (the 'haze' period), ensuring the final joint is consistent and durable.

Grouting Injection Methods for Infrastructure and Geotechnical Work

The method of introducing the grout is dictated by the soil or rock type, the depth of the target zone, and the required pressure.

Gravity Flow:

Simple, low-pressure method where grout is poured directly into large voids or pre-drilled holes, relying on hydrostatic head and gravity to carry the grout. Only suitable for surface applications and large, accessible voids.

Hand Pumping:

Used for small-scale **Structural Repair** or crack injection. A manual pump is used to inject relatively high-viscosity epoxy or chemical grout at moderate pressures into localized defects.

Mechanical Injection:

Uses high-pressure pumps to inject fluid grout into deeper zones via boreholes. This includes techniques like Tube-à-Manchette (TAM) grouting, which allows for multiple, precise re-grouting passes at the same location.

Permeation Grouting:

Injection of very low-viscosity grout (typically chemical) into granular soil or fissured rock without disturbing its original structure, filling the pore spaces to reduce permeability and increase strength.

Curtain Grouting:

A pattern of deep boreholes is drilled and grouted beneath a hydraulic structure (like a dam) to create a continuous, low-permeability **curtain** or barrier, preventing water seepage beneath the foundation.

Preplaced Aggregate Grouting:

A two-stage process where coarse aggregate is first placed in the formwork, and a highly fluid grout (a 'grout mortar') is then injected to fill the voids, creating high-quality, low-shrinkage concrete.

Specialized Grouting Techniques for Advanced Projects

Compensation Grouting Definition and Use (LSI: Compensation Grouting Definition)

Compensation Grouting is a proactive or reactive technique used to mitigate or correct ground settlement. As per its **Compensation Grouting Definition**, it involves the controlled, staged injection of grout below structures adjacent to deep excavations (e.g., tunneling). The goal is twofold:

- Control: To compensate for ground loss induced by boring or excavation, preventing settlement of structures.

- Correction: To gently lift a settled structure back towards its original elevation (often called 'Jacking').

Compaction Grouting for Soil Densification

This technique uses a very stiff, low-slump, high-mobility grout that remains in a bulb shape near the injection point. The injection pressure forces the grout bulb to displace and compact the surrounding loose granular soil, effectively increasing the soil's density, friction angle, and load-bearing capacity. It does not permeate the soil's pore spaces but physically displaces the soil matrix.

Rock (Fissure) Grouting for Dam and Tunnel Applications

Rock grouting focuses on injecting cement-based or microfine cement grouts into geological discontinuities (fissures, joints, faults) within the bedrock. The calculation governing the grout's penetration depth and efficiency is often determined by the Groutability Ratio (GR), which relates the effective particle size of the grout to the aperture size of the joint:

GR = D95 (Grout) / D15 (Fissure)

Where D95 (Grout) is the size at which 95% of grout particles are finer, and D15 (Fissure) is the joint aperture size. A GR value of < 3 to 6 is often targeted for successful penetration.

Grout Volume and Material Cost Estimator Calculator

Estimate the volume of grout required (in cubic meters) and the approximate material cost for your void filling or structural grouting project.

Calculation Results

Theoretical Grout Volume (m³): 0.00

Total Required Grout Volume (m³): 0.00

Estimated Material Cost ($): 0.00

The Lugeon Test: The Quality Control for Rock Mass Groutability

The **Lugeon Test** is the industry standard for measuring the permeability of a rock mass, a critical step before commencing **Curtain Grouting** in dams, tunnels, and other deep foundations. The results of this test determine the grout mix design, the required injection pressure, and the overall feasibility of achieving the target impermeability.

Procedure and Definition of the Lugeon Unit (Lu)

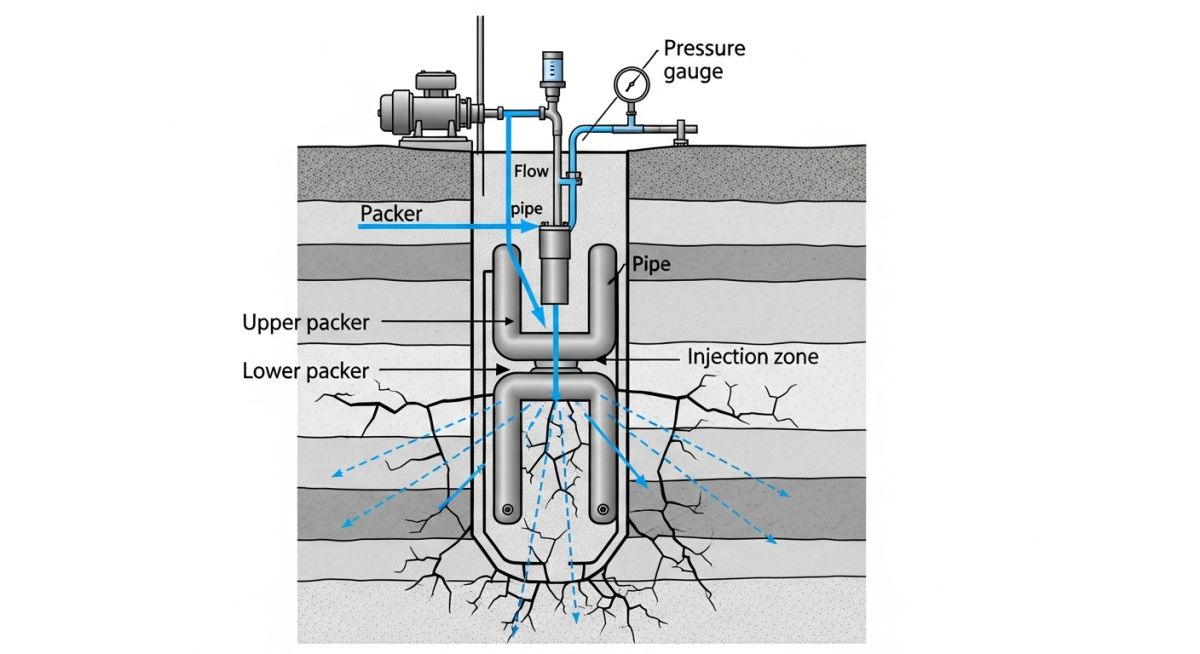

The test is performed in stages within a borehole using inflatable packers to isolate a specific section of rock. Water is injected into the isolated zone at a specified pressure for a set time, and the water intake is measured.

1 Lugeon (Lu) is defined as a water loss of 1 liter per minute per meter of borehole length under a pressure of 10 atmospheres (1 MPa).

Lu = Q / (L * P)

Where Q = Water Intake (liters/minute), L = Test Section Length (meters), and P = Applied Pressure (MPa).

Figure 3: Setup for a single-packer Lugeon test in a fissured borehole.

Interpreting Lugeon Values for Grout Design

Engineers use the Lugeon value to categorize the rock quality and determine the necessary grouting intensity. The target Lu value for final rock permeability in a project is typically set by the client (e.g., a critical dam project might require Lu < 1.0).

| Lugeon Value (Lu) | Rock Permeability Description | Grouting Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0 - 1.0 | Practically Impermeable / Very Tight | Grouting generally not required. |

| 1.0 - 5.0 | Low Permeability / Moderately Fissured | Light to Moderate grouting (e.g., single stage). |

| 5.0 - 20.0 | Moderate Permeability / Highly Fissured | Intense grouting (Primary and Secondary passes). |

| > 20.0 | Very High Permeability / Highly Cavernous | Heavy-duty grouting; Preplaced Aggregate Grouting or deep filling. |

Don't miss this video related to Piping course

Summary: Master Piping Engineering with our complete 125+ hour Certification Course: ......

Engineering Applications and Advantages of Grouting

Common Applications in Dam, Tunnel, and Foundation Work

- Dam Foundations: Curtain Grouting is essential for creating an impermeable barrier beneath gravity and arch dams to manage seepage and uplift pressure.

- Tunneling: Pre-grouting is used ahead of tunnel boring machines (TBMs) to stabilize ground, reduce water inflow, and prevent ground settlement for overlying infrastructure.

- Building Foundations: Permeation and Compaction grouting are used to improve the bearing capacity of weak soils prior to the construction of heavy-load foundations.

- Bridge Structures: Grouting column base plates and repairing voids in concrete decks and piers are common applications for high-strength, non-shrink materials.

The Key Structural and Economic Advantages

Grouting offers several benefits over traditional construction methods, particularly its ability to work in confined or deep locations with minimal disruption to adjacent structures. It provides a cost-effective alternative to deep excavation and replacement.

Case Study: Curtain Grouting Failure Analysis and Seepage Control in a Hydroelectric Dam

Figure 2: Successful post-grouting dam foundation face showing reduced weepage.

- Structure: 60-year-old Gravity Dam (Concrete).

- Problem: Increasing water seepage (Lugeon value > 5) through the foundation's highly fractured granite bedrock, threatening stability and leading to water loss.

- Objective: Reduce permeability to an average Lugeon value of 1.0 or less.

- Grouting Technique: Down-stage **Curtain Grouting** (Primary, Secondary, Tertiary holes).

The initial failure was natural: decades of water pressure widened micro-fissures (geological joints) in the bedrock. The original construction's single-line grout curtain was inadequate for the high head pressure developed by the reservoir, leading to an unacceptable **Structural Repair** requirement.

The solution involved a meticulous, multi-stage injection process using microfine cement grout, selected for its ability to permeate fissures as small as 0.1 mm. The team implemented a split-spacing drilling pattern, moving from primary to tertiary holes, ensuring maximum overlap of the grout bulbs. The process was controlled by monitoring water pressure and flow (Lugeon testing) after each stage.

- Grout Material: Type I Cement with ultra-fine particle size (D95 < 15 µm).

- Final Permeability: Average Lugeon value reduced to 0.8 across the entire dam length (exceeding the 1.0 target).

- ROI: By arresting water loss and removing the threat of hydraulic jacking and piping, the project extended the dam's service life by an estimated 50 years, saving billions in potential replacement costs.

Grout Maintenance: Cleaning and Longevity

While structural grouting is designed for permanence, exposed applications, especially for tiles and decorative finishes, require periodic maintenance to ensure longevity and appearance.

Simple Methods to Clean Grouting in Floor Tiles

Cleaning Grouting in Floor Tiles prevents the accumulation of mold and discoloration.

- Daily Cleaning: Use a pH-neutral cleaner with a soft brush or mop.

- Deep Cleaning (Mildew): A mixture of baking soda and vinegar, or a solution of water and hydrogen peroxide, is highly effective for safely bleaching and sanitizing cementitious grout.

- Chemical Cleaners: For heavy staining, an acidic tile and grout cleaner may be used, but **always test on a small, inconspicuous area first**, as strong acids can damage the cement matrix or surrounding tile finish.

- Sealing: Applying a grout sealer annually is the best defense, as it minimizes the porosity of the grout, preventing the absorption of stains and moisture.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the difference between structural grouting and chemical waterproofing grouting?

Structural grouting (e.g., cementitious or epoxy) focuses on increasing the load-bearing strength, stiffness, and stability of a structure (Structural Repair). Chemical waterproofing grouting (e.g., polyurethane or acrylate gels) focuses primarily on filling very fine cracks and reducing permeability to stop water ingress, often providing a more flexible barrier.

What criteria are used for proper grout material selection in geotechnical projects?

Proper **Grout Material Selection** depends on the size of the voids/pores (influencing the Groutability Ratio), the required final strength (G1 vs G2), and environmental factors like groundwater chemistry. For instance, fine sands require microfine cement or chemical grouts, whereas large rock voids can accept standard **Concrete Grout Mix**.

How does **Compensation Grouting Definition** differ from Compaction Grouting in application?

Compaction grouting is a soil improvement technique where grout displaces and compacts loose soil, typically *prior* to construction. Compensation grouting is a structure-specific technique often used *during* or *after* nearby excavation (like tunneling) to proactively or reactively control the settlement of specific adjacent structures.

What causes **Tile Grout Application** to crack or crumble prematurely?

Premature failure in **Tile Grout Application** is most commonly caused by improper mixing (too much water, reducing final strength), curing too quickly (e.g., due to direct sunlight or high heat), or movement in the subfloor. Using an appropriate, high-quality, polymer-modified grout and ensuring the subfloor is stable are critical preventive **Grouting Procedures**.

Conclusion: Ensuring Durability with Professional Grouting

Grouting is far more than a simple filler; it is a complex, versatile engineering solution that underpins the integrity and longevity of global infrastructure. From stabilizing loose foundation soils and mitigating the risks of tunneling to ensuring the precise alignment of rotating equipment (G2 standards), the correct implementation of **Grouting in Civil Construction** is paramount. By meticulously selecting the correct materials and injection methods—be it permeation, compaction, or curtain grouting—engineers can transform challenging ground conditions and restore the functionality of aging structures, delivering superior and lasting durability.