Alarm Management for Oil & Gas Industries: The Ultimate Engineering Guide

It is 02:00 AM. Your lead operator is staring at a DCS screen flashing with 45 simultaneous high-priority alerts. A separator level is surging, but the critical “LHH” trip alarm is buried under 300 “nuisance” chattering notifications from a faulty pressure transmitter. This isn’t just an operational headache—it is the exact precursor to a Tier 1 process safety incident. Alarm Management for Oil & Gas is no longer just a “best practice”; it is the digital frontline of asset integrity.

In this comprehensive guide, we move beyond basic definitions to explore the technical rigour of ISA 18.2 and EEMUA 191. You will learn how to transform your alarm system from a source of operator fatigue into a predictive tool for operational excellence.

Key Engineering Takeaways

- Regulatory Compliance: Implementing frameworks that satisfy [ISA 18.2 Standards](https://www.isa.org) and international safety audits.

- Operational Safety: Reducing “Alarm Flooding” to ensure operators can respond to critical events within the 10-minute window.

- Lifecycle Efficiency: Establishing a Master Alarm Database (MADB) for sustainable rationalisation and long-term performance.

What is Alarm Management for Oil & Gas?

Alarm Management for Oil & Gas is the systematic process of designing, implementing, and monitoring alarms within a Distributed Control System (DCS). It follows the ISA 18.2 life cycle to ensure every alarm is actionable, unique, and prioritized based on its potential impact on safety, environment, and production.

“Most facilities fail at alarm management because they treat it as a ‘one-time project.’ True safety comes when you embed rationalisation into your MOC (Management of Change) process. If an alarm isn’t worth an operator’s immediate action, it isn’t an alarm—it’s noise.”

— Atul Singla, Founder, Epcland

In This Technical Guide

Complete Course on

Piping Engineering

Check Now

Key Features

- 125+ Hours Content

- 500+ Recorded Lectures

- 20+ Years Exp.

- Lifetime Access

Coverage

- Codes & Standards

- Layouts & Design

- Material Eng.

- Stress Analysis

Knowledge Check: Alarm Management for Oil & Gas

Validate your expertise in ISA 18.2 standards.

Question 1 of 5

According to ISA 18.2, what is the primary purpose of an alarm?

Why Alarm Management for Oil & Gas is Non-Negotiable in 2026

In the high-pressure environment of hydrocarbon processing, the Distributed Control System (DCS) acts as the central nervous system of the plant. However, without rigorous Alarm Management for Oil & Gas, this system often becomes a liability. Historical data from major industrial accidents—such as the Milford Haven explosion—consistently point toward “Alarm Flooding” as a primary causal factor. When an operator is bombarded with hundreds of notifications per hour, the cognitive load exceeds human capacity, leading to missed critical signals and delayed emergency response.

Modern Alarm Management for Oil & Gas protocols focus on the “Actionability” of an alarm. Every alert configured in the system must represent a unique deviation from normal operations that requires a specific, documented manual intervention. By adhering to ISA 18.2 guidelines, engineering teams can transition from a reactive “firefighting” culture to a proactive state where alarms serve as reliable early-warning indicators for equipment health and process safety.

Strategic Advantages of a Robust Alarm Management System

The implementation of a comprehensive Alarm Management for Oil & Gas strategy provides more than just safety benefits; it is a significant driver of operational efficiency and mechanical integrity. A rationalized alarm system ensures that critical equipment, such as centrifugal compressors and high-pressure separators, operate within their optimal envelopes. This reduces the frequency of unnecessary emergency shutdowns (ESD), which are notoriously hard on mechanical components and lead to significant production losses.

Enhanced Operator Performance

By eliminating nuisance alarms, operators can focus on process optimization and trend analysis, rather than silencing repetitive buzzers.

Regulatory Compliance

Meeting the strict audit requirements of OSHA’s Process Safety Management (PSM) and international ISO standards for risk mitigation.

The Alarm Management Life Cycle and Rationalization Process

The Alarm Management for Oil & Gas life cycle is a continuous loop of improvement. It begins with the creation of an Alarm Philosophy—a document that defines the “rules of the game” for your facility. This includes defining priority levels (Critical, High, Medium, Low) and the specific criteria for what constitutes an alarm. The core of this cycle is the Rationalization phase, where a multi-disciplinary team (Process, Instrumentation, Operations) reviews every single tag in the DCS to validate its setpoints and consequences of inaction.

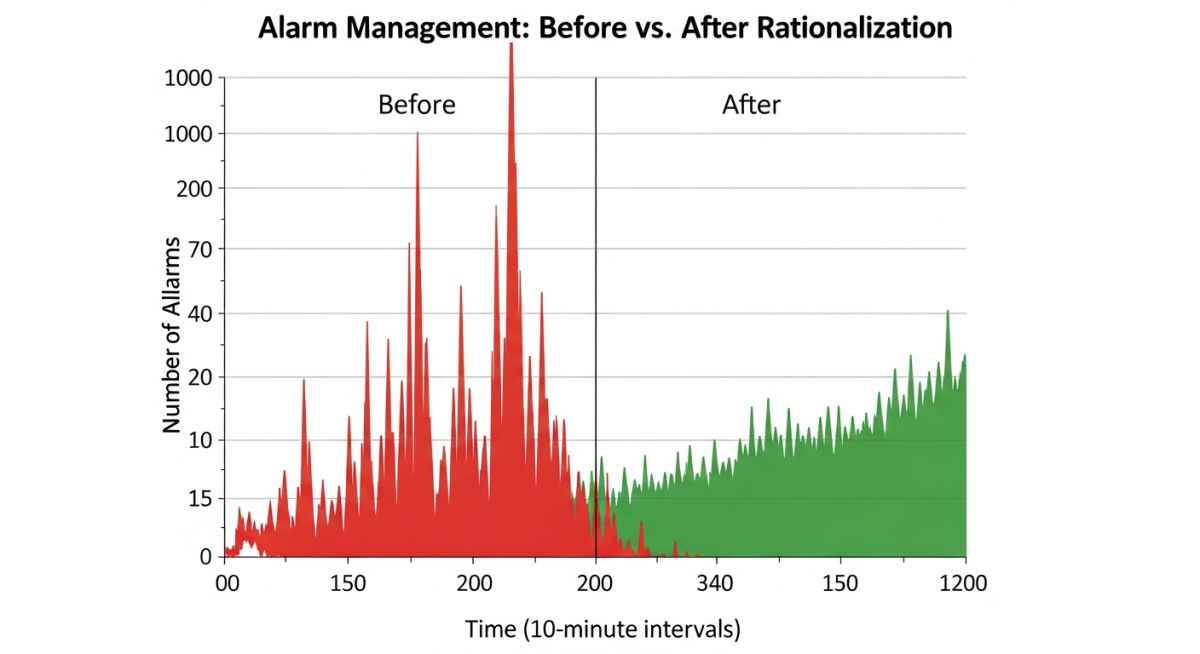

During rationalization, engineers identify “Bad Actors”—alarms that activate more frequently than the system’s threshold. Common culprits include chattering sensors, which oscillate rapidly between states, and stale alarms that remain active for days. By applying deadbands, on/off delays, and proper suppression logic, the total alarm count can be reduced by up to 80%, providing the operator with a “Quiet Control Room” environment.

7 Key Steps for an Effective Alarm Management System

To achieve world-class Alarm Management for Oil & Gas, facilities must transition from haphazard setpoint entry to a structured engineering workflow. This workflow is governed by global standards, primarily ISA 18.2 and EEMUA 191, which provide the framework for reducing operator cognitive load and preventing “Alarm Fatigue.” Below are the technical stages required to build a resilient system.

Step 1: Alarm Philosophy Development & Implementation

The bedrock of Alarm Management for Oil & Gas is the Philosophy Document. It defines the “Legal Code” for alarms, specifying color schemes (e.g., Red for Emergency, Yellow for High), required response times, and the technical criteria for alarm suppression during plant start-up or shutdown.

Step 2: Alarm Performance Benchmarking against ISA 18.2

You cannot manage what you do not measure. Using DCS historians, engineers must calculate the Average Alarm Rate. For a stable plant, the target is less than 1 alarm per 10 minutes. Anything higher indicates a system in distress.

Step 3: Resolution of “Bad Actor” and Chattering Alarms

“Bad Actors” are the top 10 most frequent alarms. In Alarm Management for Oil & Gas, these are usually chattering sensors. Resolution involves applying Hysteresis (Deadbands) or On/Off Delays to prevent a signal from flickering due to process turbulence.

Step 4: Technical Alarm Documentation and Rationalization (D&R)

Every alarm is reviewed by a multi-disciplinary team. We document the Consequence of Inaction and the Operator Action. If no action is required, the alarm is removed or converted to a status event.

Comparison of Alarm Performance Metrics (ISA 18.2 vs. EEMUA 191)

| Metric Category | Standard: ISA 18.2 | Standard: EEMUA 191 | Industrial Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. Alarms (Normal) | ~1 per 10 mins | < 1 per 10 mins | < 144 per day |

| Peak Alarms (Flood) | > 10 per 10 mins | > 10 per 10 mins | Zero Floods |

| Priority Distribution | 3-4 Levels | Emergency/High/Low | 80% Low / 5% Critical |

| Stale/Standing Alarms | < 5 per console | < 10 per console | < 5 Total |

The remaining steps—Audit, Real-time Management, and Maintenance—ensure that the rationalized state is “Enforced.” This prevents “Settings Creep,” where operators or technicians slowly change setpoints over time, degrading the safety integrity of the Alarm Management for Oil & Gas system.

Don’t miss this video related to Oil & Gas

Summary: Master Piping Engineering with our complete 125+ hour Certification Course: ……

Alarm Performance & Fatigue Calculator

Benchmarking your facility against ISA 18.2 and EEMUA 191 standards.

Engineering Tool powered by Epcland Architecture

Alarm Management for Oil & Gas Failure Case Study

The Scenario: The "Silent" Flare Header Overpressurization

In a major offshore production platform, a sudden trip of the main export compressor triggered a massive pressure surge in the flare header. Within 120 seconds, the Distributed Control System (DCS) generated over 450 alarms. Among this digital "noise" were critical notifications regarding the Flare Knock-Out (KO) Drum High-High Level (LAHH).

The Failure (Pre-Rationalisation)

- Alarm Fatigue: The operator was acknowledging alarms at a rate of 1 per second, physically unable to read the descriptions.

- Priority Smearing: 60% of active alarms were marked as "High Priority," making it impossible to distinguish between a pump trip and a vessel rupture.

- Nuisance Chattering: A vibrating level transmitter on the KO drum had been chattering for 3 days, leading the operator to "ignore" its frequent flashes.

The Solution (Post-Rationalisation)

- Dynamic Suppression: Implemented logic that suppressed non-critical alarms (e.g., lube oil low pressure) automatically when the main compressor trips.

- Alarm Shelving: Authorized operators to "shelve" known faulty instruments for 8-hour shifts, removing chattering noise from the HMI.

- ISA 18.2 Priority Audit: Re-classified alarms so that only 5% of the total database carried a "Critical" status.

Outcome & Engineering Lessons

The incident resulted in a liquid carryover to the flare tip, causing a "rain of fire" on the sea surface. Following a rigorous Alarm Management for Oil & Gas audit, the facility reduced its average alarm rate by 82%. The engineering team learned that Alarm Management is not a software setting, but a human-factors discipline. By ensuring that the LAHH alarm was the only red notification on the screen during a trip, they guaranteed an operator response time of under 30 seconds for future events.

Expert Insights: Lessons from 20 Years in the Field

- Priority is Relative: If everything is "High Priority," then nothing is. Limit your "Critical" alarms to less than 5% of the total configured database to ensure operator focus during upsets.

- The "Action" Litmus Test: During rationalization, if the team cannot define a specific manual action for an alarm, it must be removed or converted to a "Journal Event" in the DCS historian.

- Dynamic Suppression is Key: In Alarm Management for Oil & Gas, use state-based alarming. If a pump is intentionally stopped, its "Low Discharge Pressure" alarm should be automatically suppressed to prevent HMI clutter.

- Audit the "Stale" Alarms: A standing alarm that stays active for more than 24 hours is no longer an alarm—it is a maintenance backlog item. These must be addressed via the Master Alarm Database (MADB).

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I stop my operators from ignoring critical alarms during a flood?

You cannot train an operator to handle a flood; you must engineer the flood out of the system. Implement ISA 18.2 compliant alarm shelving and dynamic suppression so that only the "root cause" alarm remains visible during a trip.

Is it safe to "shelve" or suppress alarms in a hazardous Oil & Gas facility?

Yes, provided it is done through a controlled "Alarm Shelving" function with time limits and audit trails. Suppressing a "chattering" nuisance alarm actually increases safety by allowing the operator to see genuine process deviations.

What is the first step if our facility currently has no Alarm Philosophy?

Conduct a "Bad Actor" analysis. Identify the top 10 tags causing the most alarms over the last 30 days. Fix these technical issues first while simultaneously drafting your Philosophy document based on EEMUA 191 guidelines.

What is the difference between an Alarm and an Alert?

An Alarm requires an immediate operator action to prevent a consequence. An Alert (or notification) provides process information or status (e.g., "Pump B Started") that does not require an urgent response.

How often should an Alarm Audit be performed?

ISA 18.2 recommends a comprehensive audit every 3 to 5 years, but performance monitoring (benchmarking) should be a continuous or monthly process to catch "Bad Actors" early.

What is a Master Alarm Database (MADB)?

The MADB is the authorized "Source of Truth" for all alarm settings. It contains the rationalized setpoints, priorities, and consequences documented during the D&R phase.

References & Standards

- [ISA 18.2: Management of Alarm Systems for the Process Industries](https://www.isa.org)

- [EEMUA 191: Alarm Systems - A Guide to Design, Management and Procurement](https://www.eemua.org)

- [IEC 62682: Management of Alarm Systems for the Process Industries](https://www.iec.ch)

- [API RP 754: Process Safety Performance Indicators for the Refining and Petrochemical Industries](https://www.api.org)