The Hidden Heat of Compression

Exploring a critical engineering rule-of-thumb: why is most of the energy fed into a large gas compressor converted not into work, but into waste heat?

The 90% Assumption

In preliminary engineering design, a standard assumption is that 90% of the electrical energy supplied to a compressor is dissipated as waste heat. This seems counterintuitive, but it’s a sound estimate rooted in thermodynamics.

Only about 10% of the input energy performs the “useful work” of increasing the gas pressure. The rest must be safely removed.

Where Does the “Waste” Come From?

The “waste heat” isn’t from a single source but is the sum of several systemic inefficiencies.

Thermodynamic Inefficiency

The primary contributor. Compressing a gas inherently increases its temperature (heat of compression) in addition to its pressure. This is the largest source of heat.

Motor Inefficiency

Even highly efficient industrial motors (95-97%) convert 3-5% of electrical energy directly into heat due to electrical resistance and friction.

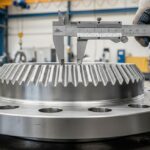

Mechanical Inefficiency

Frictional losses in bearings, gears, and couplings between the motor and compressor contribute another 1-2% of energy as heat.

The Consequence: A Catastrophic Temperature Rise

If this massive heat energy (e.g., 9,026 kW for an H₂ compressor) isn’t removed, what happens? Let’s calculate the theoretical temperature increase if compression from 2 to 25 bar were done in a single, uncooled step.

Inlet Temperature

40°C

Calculated Outlet Temp

494°C

Temperature Increase

+454°C

A ~500°C outlet is completely unacceptable and dangerous, leading to:

The Engineering Solution: Multi-Stage Compression

To prevent catastrophic heat buildup, vendors use a standard, elegant solution: breaking the compression into multiple stages, with cooling in between each step.

Gas In (40°C)

Stage 1 Compressor

Intercooler

Heat Removed

Stage 2 Compressor

Intercooler

Heat Removed

… Final Stage

Aftercooler

Final Cooling

Gas Out (40°C)

Benefits of this Design

Calculate Your Own Temperature Rise

Use the calculator below to see how different parameters affect the final outlet temperature, based on the same thermodynamic principles.

Polytropic Exponent ($n$)

–

Calculated Outlet Temp ($T_{out}$)

–

Total Temperature Increase ($\Delta T$)

–